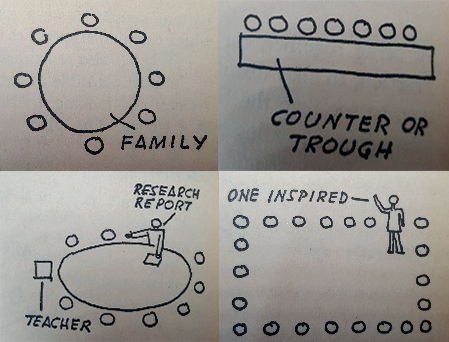

You can sit for liberty or for authority. Eating, Paul Goodman (1911-1972) noted, was one such activity whose seating arrangements could either nurture fellow-feeling or cement and reinforce hierarchy. A family may ‘cement’ its bonds by clustering around a circular table. Nobles may sit with the King at a feast, advertising their power in their proximity to the hungry monarch. Or, in a culinary manifestation of Taylorism, an individual may eat alone at the counter of a diner, sitting before the ‘trough’ with other equally isolated souls. From therapy to religious congregations, Goodman saw that the seating arrangements adopted in any social settings shaped their unfolding: the out-of-view Freudian therapist guides the patient in exploring their unconscious; the Quaker circle removes ministerial authority to allow the community to follow the spirit’s inspiration; the university ‘roundtable’ facilitates ‘face-to-face […] collaborative thought’. For Goodman, these arrangements highlighted the importance of thinking about how we can sit for liberty.

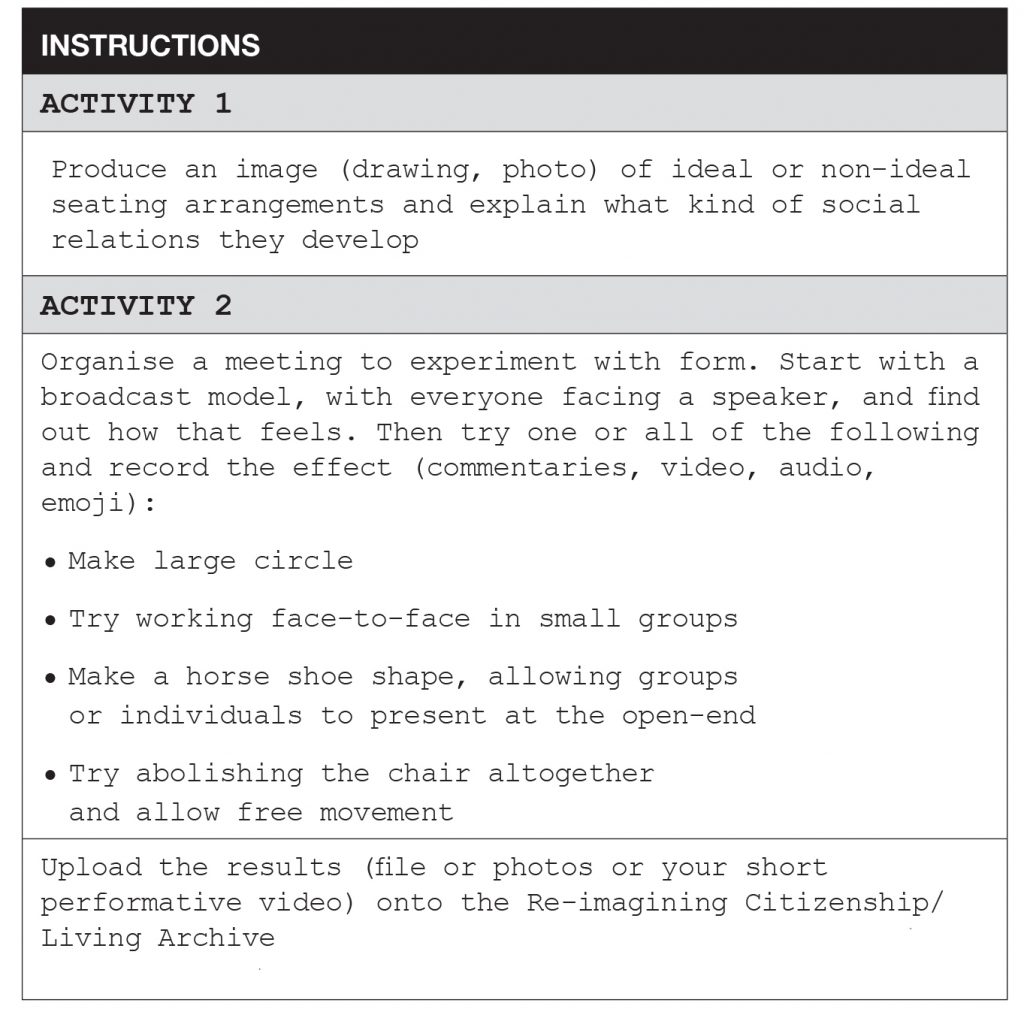

Citizenship presupposes activity: how do our environments impede or facilitate good citizenship? What do our seating arrangements encourage?

Goodman believed, that empowered citizens would create a more democratic and liberated world. The liberation of space was an essential component of this, and the liberation of seating was a good first step.

In Situ Citizen Adams

Matthew Adams is Lecturer in Politics, History and Communication at Loughborough University where he both sits and stands. His most recent publication is The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism (2019) with Carl Levy, and he is currently working on the concept of civic virtue in anarchist political thought. For this he is usually seated.